An Unconventional Childhood – Growing Up with Deaf Grandparents

This is a personal story about an unconventional childhood. Maybe “unusual” childhood is a better description. It begins way back in 1942 when I was 2 years old and my parents were in the midst of an unpleasant divorce. While my parents were engaged in drawn-out skirmishes over custody for my older brother and me, we were sent to live with my grandparents in Denver, Colorado. The unusual part of the story is that my grandparents were totally deaf. And I mean rock-stone deaf – no measurable hearing and no hearing aids in those early days. The communication between them was solely by American Sign Language (ASL). My brother and I arrived at their home to meet them for the first time and realized that we had no means of talking with them.

At that time my grandparents were in their early 60s and probably not prepared to take on the tasks of rearing two young, wild grandsons for an undetermined length of time. Both grandparents had been deaf since their childhood. Both had lost their hearing through childhood episodes of cerebrospinal meningitis which spread as a near-epidemic during the 1880s. Common health issues resulting from meningitis include blindness and severe cardiac problems; profound hearing loss is the most common adverse outcome experienced by some 50% of those stricken. The hearing loss of my grandparents was, fortunately, the only health issue they suffered following recovery from this serious infectious disease.

A major difference between my grandparents was that my grandmother lost her hearing at age 6 months – within the period that we now identify as pre-lingual. In contrast, my grandfather was 9 years of age when he lost his hearing – so he was post-lingually deafened. Accordingly, their speech skills were dramatically different from each other. My grandmother, having never heard herself or others speak, was always reluctant to use her noticeably deaf speech outside our home environment and was sensitive about her limited language skills. My grandfather, on the other hand, with a significant amount of normal hearing for speech and language development in his early childhood, had near-normal voice quality and good language skills. Although from different states in their childhood, both attended Gallaudet College (for the deaf) in Washington DC from 1889 – 1902 where they met and married after graduation.

As an aside to my story, a bit of history may be of interest. Until the mid-1940s, persons with profound deafness were commonly known as “deaf and dumb” or “deaf-mute.” The “dumb” and “mute” terms were related to the view from outsiders that the deaf could not speak because they chose to communicate in signs. In those early years, these terms were not necessarily derogatory, but actually socially acceptable. In fact, my grandfather referred to his deaf friends as his “dummie friends.” The manual sign for deafness was conveyed by pointing to the ear, pointing to the mouth, and making the sign for “closed.” Whereas, the sign for a hearing person was fingers moving forward from the mouth – as in speaking. The first school for the deaf in the US was established in Hartford in 1817 and was named The Connecticut Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb. In the following years, states established their own schools for educating the deaf with support from the federal government. Because many deaf children had to travel some distance to attend the state school, the schools were often residential and from early in their lives the students studied and lived on the school campus. So in the case of my family, my grandfather attended and was a resident of the Kentucky School for the Deaf in Danville and my grandmother grew up at the Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind in Colorado Springs.

The question often asked is how did I learn speech and language at age 2 in a home that was silent? The answer, of course, is that this home was far from silent. My brother and I communicated normally – in whatever terms an 8-year-old might talk to a 2-year-old. Both grandparents spoke to us orally as best they could. I have been told that I enjoyed having my grandmother read to me in spite of her poor vocal qualities. And, apparently my brother and I picked up the manual language of signing and fingerspelling quickly. Although I was too young spell words, the sign language was sufficiently illustrative for me to get my needs and thoughts communicated. We were largely entertained by the radio that my grandparents purchased for us. The radio turned out to be language rich with nightly serial stories such as The Green Hornet, Amos and Andy, The Lone Ranger, the spooky mysteries of Inner Sanctum, and the comedy of Edgar Bergan and his puppet, Charlie McCarthy. Saturday morning radio was aimed at children with shows such as Let’s Pretend, Sky King, Terry and the Pirates, and Dick Tracy. Apparently, I entertained my grandparents by enthusiastically trying to tell them through pantomime and signs what I was listening to on the radio.

It is a common misperception is that the hearing children of deaf parents have trouble learning spoken language. There have been reports of delayed and inadequate language acquisition from such children. However, I quickly became “bilingual,” i.e., learning American Sign Language and spoken English at the same time. As the hearing child of deaf grandparents, I really lived within two languages and two cultures. I had my own normal hearing family and friends and mixed well within the circle of deaf friends of my grandparents. As a preschooler, it was a matter of making pictures and signs with my hands in the language of my grandparents; at the same time learning to speak words and sentences by listening to visitors, the radio, and ultimately kindergarten.

In the homes of deaf persons, you will find a few peculiarities. For example, the doorbell not only “rings” but it is often hooked into the lighting system of the household so that lights in each room blink on and off as the doorbell is pressed. A very loud alarm clock also vibrates the pillow and may flash a light on and off to awake the deaf sleeper. We had a wonderful mutt of a dog who was likely the first “hearing service dog” before that concept was developed. Our dog, General, seemed to understand that my grandparents could not hear. He served as their daily “ears”. Certainly no one could approach our house without General sounding the alarm – or even pulling one of them to the front door. One gets the attention of a deaf person by casually waving a hand or wildly waving an arm and hand to gain immediate attention for more important matters. As persons with deafness are extraordinarily aware of vibration, stomping on the floor can also be used as an attention gaining behavior. To ignore someone, you simply refuse to look at them.

Early on I learned that I could be of great help to my grandparents by serving as an interpreter. By the age of 3, relatives tell me I would hear the weather forecast on the radio and pass it on to my grandmother through signs and facial expressions. By the age of 4, and thereafter throughout life, my job was to accompany and interpret for them. It made me feel very grown up and mature – and I remember how surprised the clerks were to see me conversing in signs. Our grandparents had a telephone installed in the house so that my brother and I could place phone calls for them – making their lives easier. For the most part, being their interpreter seemed a normal part of my life. Perhaps it forced me to mature sooner than my peers. Being dragged everywhere your parents went so that you could interpret for them (e.g., the post office, doctor's appointments, the driver’s license bureau, the courtroom, etc.) tends to involve one in a number of grownup things that most children are not exposed to until their adult years. Such children (known today as CODA – Children Of Deaf Adults) learn spoken language as a natural part of growing up; however, they are naturally required to navigate the border between the deaf and hearing worlds, operating as a liaison between their deaf parents and the hearing world.

Of course, my deafness connection caused me no end of embarrassment during my teen years. I had to often accompany my grandparents and openly sign and communicate for them. What if any of my friends would see me? And, it was a difficult situation to be put into when my grandfather was angry over some issue and I had to transmit his words and feelings to someone else. I was in middle school before I realized my friends thought my skills with ASL were “pretty neat.” Many young people try to learn the manual alphabet with thoughts of secret communications with friends; however, few of them ever become sufficiently skilled to actually carry on more than a word or two in conversation. It was with some pride when I finally realized that my ASL abilities were viewed as a talent and brought me special recognition.

There were a number of memorable events related to their deafness. At about age 16, I was eating in a restaurant with my grandparents and, of course, we were talking to each other through ASL. I was aware of an older couple intently watching us from a nearby table. As they finished their meal, the woman come over to my grandfather, tapped him politely on the shoulder and said to him, “I think it is wonderful what you are doing for this young boy.” As he could not understand what she was saying, it fell to me to tell her that he was the deaf person and I could hear just fine. She was suddenly so embarrassed she turned and fled without another word. I also recall the occasion when a group of my high-school football buddies were invited to my home for dinner served by my grandparents. After a time, one of the friends asked me, “How do you know they are not faking and actually listening to everything we are talking about?” To test this question, the guys casually dropped some swear words that should never be used at any dinner table; when my grandparents did not respond or show interest, the dinner situation unfortunately descended into deplorable conversations – much to the amusement of my depraved friends.

People with normal hearing are able to reflexively adjust the volume of their voice according to the presence of background noise. I smile now as remember my grandfather attempting to whisper to me in the midst of a seriously quiet church moment, but unfortunately loudly voicing his message to me so that all could hear him. On the other hand, in a noisy situation he was unaware that he needed to speak with a louder voice. In somewhat the same regard, I shudder as I remember him driving slowly to a crawl to turn a corner, blissfully unaware of the honking horns and screeching brakes of the drivers behind him.

They are both gone now having lived healthy and happy lives. Yes, they often mentioned how frustrating it was to be deaf, yet they managed living every day to the fullest. My grandfather had a successful printing business in downtown Denver. Their social life involved groups of deaf friends who played cards together, went bowling, picnic outings, and church activities. Their deafness did not hold them back from experiencing most of the activities of normal hearing persons. In today’s technical environment they would have likely been among the earliest to step up for digital hearing aids and cochlear implants; visual-voicing devices and texting would have been such an incredible benefit for them.

My family evolution is notable for having four generations involved with deafness and hearing loss as both my aunt and my daughter are certified teachers of the deaf. As for me, being a child raised by loving deaf grandparents created many opportunities as I pursued a career of more than 50 years in various aspects of audiology. Fondly looking back now in my near-retirement years, I owe much to my deaf grandparents for making my “unconventional childhood” so exceptional.

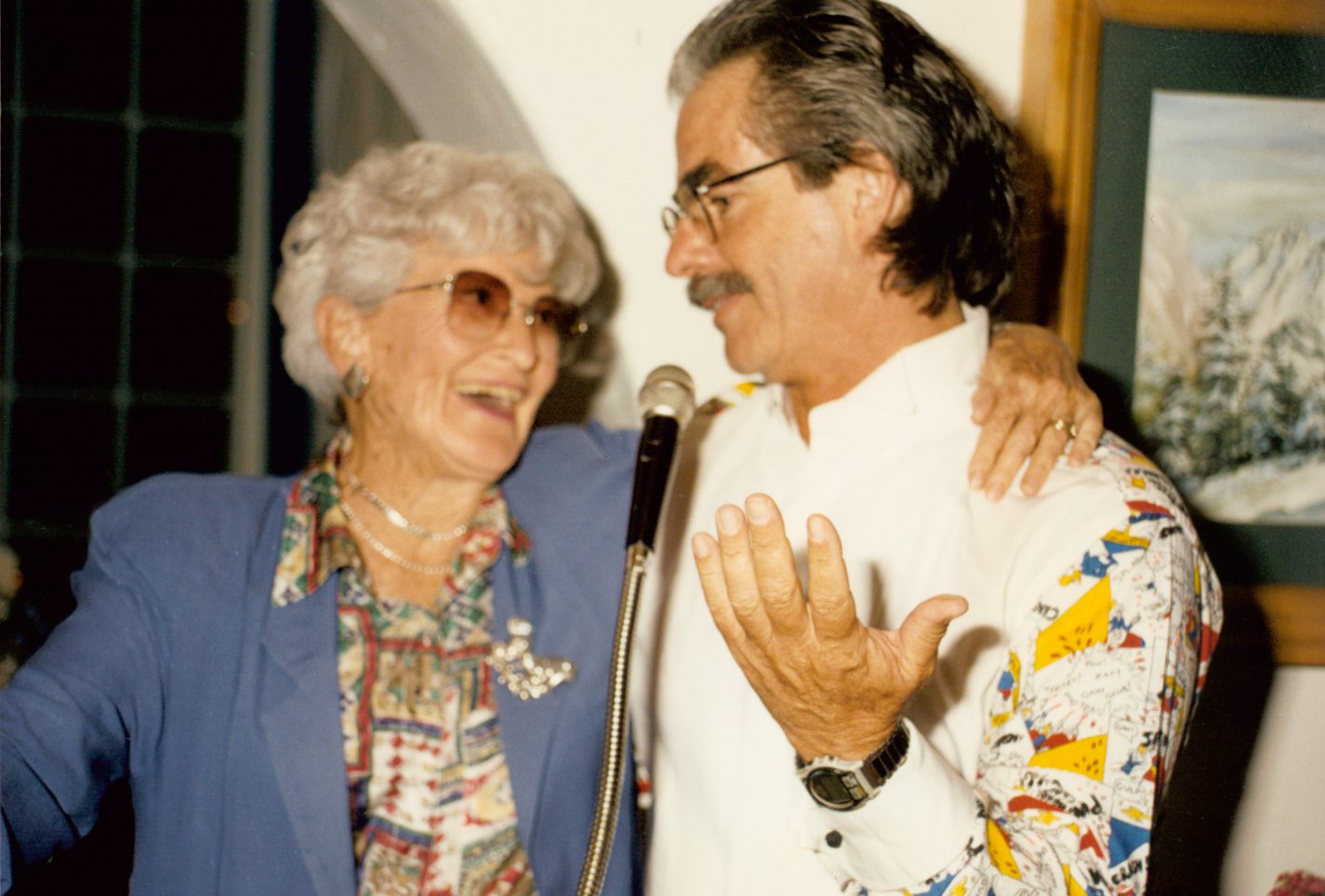

Marion Downs with Dr. Jerry Northern.